After Kathmandu by Truck, I was truly addicted – to both travel and writing. My head filled with plans for the next trip, the next book. My spirit of adventure knew no bounds; my publisher was willing. All I needed was a companion. I persuaded an old school friend to join me on a 4-month backpacking trip starting with the Trans-Siberian Railway, then a boat to Japan and travels around various S.E. Asian countries.

Despite meticulous planning, our trans-Siberian journey almost didn’t happen. Two days before our scheduled departure date, we were still awaiting visas, having applied months before. This was ‘normal’, we learnt, permission to enter the USSR being an arbitrary matter back in 1975. This was later verified by some of the other foreign passengers who had tried several times before having their applications approved.

Thanks to a frantic, last-minute, overnight journey from Norwich to the Russian Embassy in London by my friend, we were granted our visas with only a few hours to spare before leaving. After this nail-biting introduction, Russia could only get better. We were not disappointed. Spending two weeks on a train was more fun than I’d ever imagined.

The whole journey had a slightly surreal flavour. This was partly to do with the discrepancy between official and local time. The train’s timetable, displayed in each carriage, was based on Moscow time but as we travelled east, this got more and more out of sync with the local time – by as much as eight hours eventually. The dining car also worked on local time. It was confusing when at 3pm official time it was already dark and at 1am still light. Adding to the confusion was the backwards progress from autumn into summer as our journey took us towards the Pacific. The vastness of the landscape, its desolation and remoteness, especially after entering Siberia, offered us a very different perspective to that of Europe.

We were sharing our compartment with a chain-smoking Swiss woman and her husband who, we discovered the first night, had a wooden leg. We knew nothing of this until we were asked to leave the compartment so that he could unstrap it in privacy before going to bed. Next door was K, a predatory German who lived on a Pacific island and whose endless boasting soon earned him the nickname of ‘Superman’. He pestered me continually, making crude suggestions with a corncob bought from one of the peasant women selling local produce at stations along the route. Fortunately for me, at an overnight stop in Khabarovsk, he got his way with an Intourist guide called Olga (or so he bragged) and, much to my relief, stopped his harassment.

We had been issued with vouchers for the dining car. Its extensive menu in several languages listed a huge choice of dishes but few had prices, the vast majority being marked ‘not available’.

Billboards featuring Lenin appeared at every station while literature stands on the train ensured that passengers were supplied with plenty of appropriately uplifting reading matter on the benefits and achievements of the socialist state. However, we found that the views expressed were not shared by all. One morning K showed me a note deposited on his bed by a fellow-passenger, a Russian who had left the train during the night. It was headed ‘Ich bin antikommunist’ and followed by a long diatribe in Russian against the system. At that time I still remembered some of my university Russian – enough to get the gist of the message. Perhaps unwisely, I showed it to Irma, a teacher of English with whom I had made friends over the previous few days (and continued to correspond with for the next 20 years). She was shocked and claimed he was an illiterate and maverick. Just as well because moments after she had translated it for me, the controller of the train’s recorded music output (mostly patriotic songs) entered the compartment and proceeded to question her. There could be only one explanation: the train was bugged.

Intourist representatives met us at stations along the route. They always knew who we were and where we were going. Individuals like us (rather than the more controllable organised groups) were seen as suspect. Looking back, the stern communist regime that seemed rather sinister at the time now looks almost quaint compared to today’s corrupt mafia-style capitalism in Russia and elsewhere.

After a night in Khabarovsk, where the Rossiya train terminated, a team of twelve Mongolian boxers joined us on a more lavishly appointed train, furnished in grand Victorian style though built much later. The last part of the route sped us through the night – if I remember rightly, we were partying at the time with a group of card-playing Russians – along the militarised border with China, to the port of Nakhodka. It was there that we boarded our surprisingly luxurious ship, the Felix Dzerjinsky, and set sail for Yokohama.

We travelled on plenty more trains during our 4-month trip, from the super-fast, super-efficient, super-clean Japanese bullet train to the filthy, overcrowded, third-class Indonesian carriage in non-A/C tropical heat. More in my next blog post!

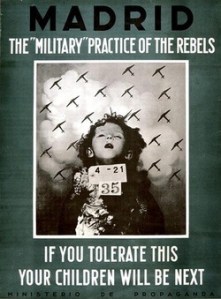

I’m loving all the research for my current work. Much of it involves reading but I’ve also made visits – to the Museum of Everyday Customs in Antequera, to the battlefield of Jarama, to a former Civil War hospital at Tarancón.

I’m loving all the research for my current work. Much of it involves reading but I’ve also made visits – to the Museum of Everyday Customs in Antequera, to the battlefield of Jarama, to a former Civil War hospital at Tarancón.