Writing a novel set in the fairly recent past in a country not my own but where I’ve lived for 18 years presents a few extra challenges. My work-in-progress (provisional title The Red Gene), spans the years between 1936 and 2012 and moves between various parts of Spain and England. Secrets of the Pomegranate was also set in Spain but, apart from the earlier diary excerpts, coincided with my time in Granada, which made it much easier: the setting was familiar territory.

Before embarking on the writing of The Red Gene, I had to read widely, interview quite a number of older people (in Spanish) and trawl the Internet. But the need for research doesn’t disappear when you start writing. Almost every day, questions arise – minor details that have to be checked. Were boys and girls taught separately in Cañar’s school in the 1920s? When did they stop bandaging babies’ tummies after birth? Where did people in Antequera go for excursions on feast days and what food did they take? What do they call the fish-shaped banner carried in the Easter processions? With recent history, one needs to take particular care, as there are still plenty of people living who would spot any mistakes or anachronisms. Getting these finer points right is essential. As a reader I’m not only annoyed if I spot errors; I’m also less likely to be convinced by the story.

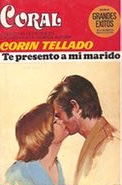

This is not unique to a historical or a foreign setting, of course. Every novelist has to check facts, chase up minutiae. Google and Wikipedia make research a lot easier but they have their limitations and that is where personal contacts come in. They are a rich resource, the key to more first-hand and anecdotal information. The advantage of having lived in Granada for so many years, building up friends and acquaintances (as you do), is huge. A word here or there is enough. If I’m not personally acquainted with a native of Cañar or a midwife, for example, someone I know will be. Someone will remember what books or magazines the older females in their family (those who were literate) were reading in the 1960s.

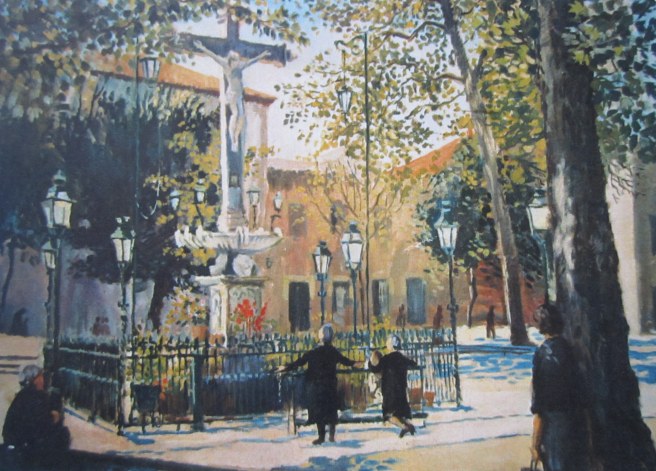

Knowing whom to turn to for the answers to all those small but important questions is vital. I would never have known from the usual channels about the women in mourning black who prayed to the Cristo de los Favores in Granada’s Realejo district had not my artist friend Allan Dorian Clark, who lived there in the 60s, told me (see his painting below). Nor about the poor people who lined up every Saturday morning at the house of a well-to-do businessman (Esperanza’s father) for a coin that would enable them to eat.

I needed contacts for the English sections of the story too. For example, the father of Rose, my main protagonist, was a vicar. To glean more information about a vicar’s household in the 1930s and 40s, I consulted my friend John, whose father was a vicar in England at that time.

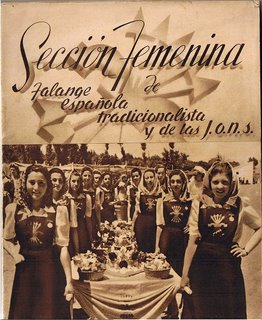

In Spain, my doctor friend Rosa could confirm that my account of dealing with a sudden heart attack in the late 1930s was realistic; members of my walking group knew in which areas the maquis (guerrilla fighters) were active in the years after the Civil War. The parents of my pilates teacher Javi are from Antequera, where Consuelo (another main character in my novel) grew up, and could give me an insight into life there during the dictatorship; Pepita, a midwife in the 1950s, could describe her travels to remote parts of the province to attend births. From Allan, who belongs to several of the religious cofradías (brotherhoods), I could glean an inside view of their activities.

I have friends or friends of friends who come from families on the left and (a few) on the right. A bus driver from the village of Cañar, where the family of Rose’s lover Miguel lived, told me of two histories of the village written by natives, one a relative of his. I talked to Spanish nurses, to a retired labourer and to the daughter of a Republican who had disappeared into hiding for most of the Franco decades.

So in this post, I want to offer a massive thank you to all the friends and acquaintances who by furnishing me with the authentic detail I needed, helped bring my story alive.