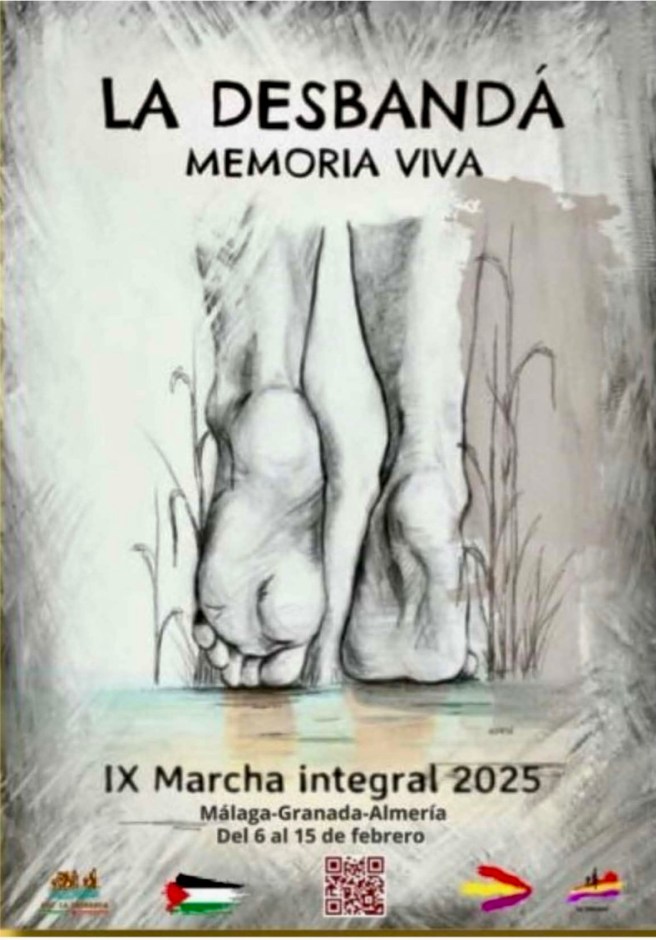

Known as La Desbandá, the ten-day march I joined for a day this month, saw hundreds of people walking along the hard shoulder of the N340 highway and along beaches and footpaths on a 220km route along the southern coast of Andalucía. We were walking in the footsteps of the 300,000 refugees, two thirds of the population, who set out from Málaga and other towns and villages in February 1937 in the civil war that had followed the previous year’s attempted coup d’état. These refugees were fleeing the imminent arrival of Franco’s troops under General Queipo de Llano, whose terrifying threats were broadcast repeatedly on the radio. Their desperate hope was to reach the provinces to the east, still under Republican control.

The political and military leaders of the Republic had already abandoned Málaga and knowing the fate awaiting them, panicked families took to the road, carrying what they could, some with their mules or donkeys, many with babies in arms, small children, the elderly and the sick. Starving, crippled, exhausted, they trudged on, many barefoot with terrible sores on their feet. As they walked, bombs were rained down on them from German planes, from Spanish warships and from the tanks and troops of the Italian and Moroccan armies supporting Franco. At least five thousand died on the road, later renamed the ‘Road of Death.’ Some died from exhaustion, cold or hunger or from their wounds; many more from the bombing. Those who continued had to abandon not only their meagre belongings but also their dead, most of whom were children, the elderly and women.

Some were more fortunate, saved by the arrival of a Canadian doctor, Norman Bethune, famous for his pioneering blood transfusions, along with a battalion of the Republican army and two of the International Brigades, who gave some protection at the front and rear of the trail of refugees. A memorial plaque in Norman Bethune’s honour can be seen in Velez Málaga.

Marching in the Desbandá, an annual event since 2017, was an emotional experience. The terrors and physical hardships endured by the refugees in 1937 played constantly in my imagination. No way can the commemorative march be compared, but neither is it an easy walk. Those completing the whole distance march up to twenty kilometres a day, sleeping on the floors of sports centres along the route. Many of the hundreds of participants were in their sixties and seventies or older. Some had been among the refugees of 1937, small children at the time. Many others were the children or grandchildren of survivors and had family stories, moving testimonies of what happened to their relatives.

In one part of my novel, The Red Gene, English nurse Rose is working with some of the victims in a convalescent hospital in Murcia. She speaks of the trauma and suffering of the children and their mothers, the physical and mental effects of their experiences.

‘Franco, Señorita, Franco!’ The little boy clutched at Rose’s uniform as the air raid siren sounded its ominous screech. The children leapt out of their beds, running to her in terror. The nightmare of their retreat from Málaga was still with them. Rose could not erase from her mind the horrific scenes described by the mothers of these children – those who had survived. The nightmare of being attacked from air and sea, machine-gunned and bombed as they fled with what possessions they could carry on their backs or in overloaded carts. The nightmare of seeing men, women and children dead or dying in ditches, mules lying feet up in the air by the roadside.

Almería and Murcia were now swamped with refugees. Attempts to distribute them around neighbouring villages and set up children’s colonies had been partially successful. However, the local population had scarcely enough to eat and with such an influx, malnutrition was rife. Rose was horrified to see a four-year old boy with limbs no bigger than those of a six month old baby. Where there should have been muscles, repeated hypodermic injections had caused the most awful abscesses.

The purpose of the annual march is not only as a homage to the refugees of the Civil War but also to bring to attention this genocide, largely forgotten or ignored, and to demand justice and reparation for the victims. It was the first case of a deliberate and indiscriminate massacre of the civilian population, repeated numerous times since and now seen in the terrible genocide in Gaza.

This year the entire route of the Desbandá was declared a Site of Historical Memory. Too much of Spain’s history of atrocities has been buried and forgotten. In today’s world, threatened by the rise of fascism, nationalism and authoritarianism, it is vitally important that we remember and honour the victims so that such horrors are not repeated.