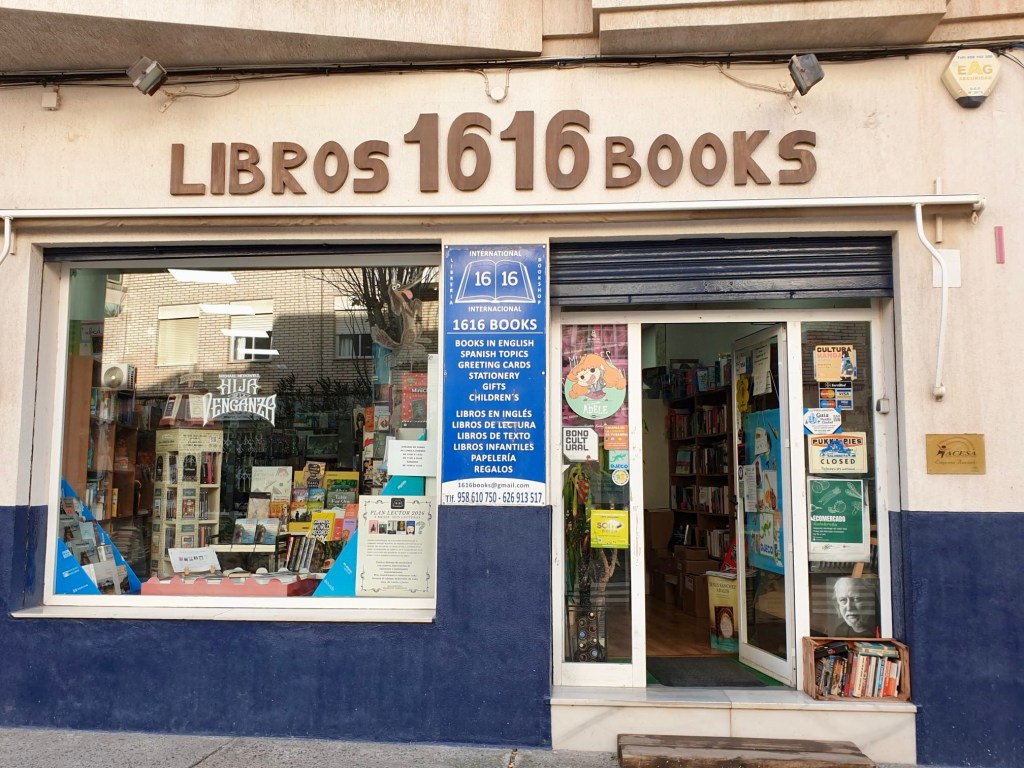

Cuando pensaba en mudarme fuera de Granada y buscaba otro pueblo donde vivir, tuvé varios motivos por elegir Salobreña. Pero sin duda uno de ellos fue la Librería 1616 y su amable dueño, Antonio Fuentes Casas. Es pequeña pero en mi opinión es una librería sin igual. Conocí a Antonio hace muchos años. Cada vez que bajé a la playa, pasé por su librería para comprar libros, mirar las novedades o simplemente hablar con él. Muchas veces tenía recomendaciones interesantes.

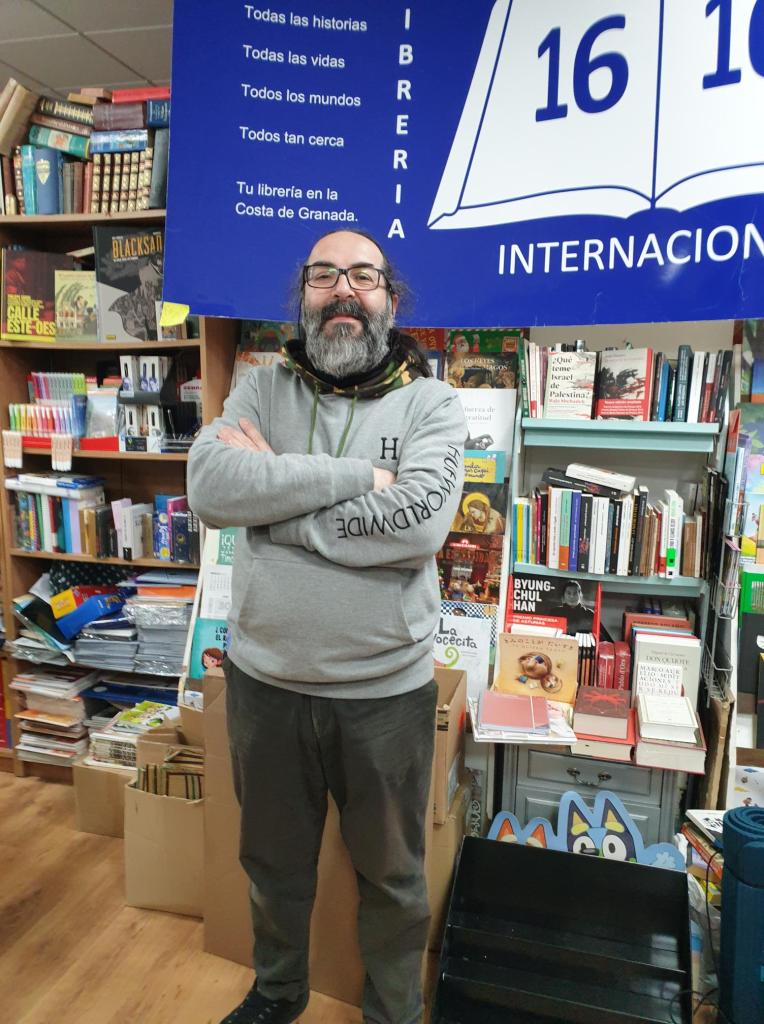

Ahora, vivo muy cerca y veo que es mucho más que una librería. Tiene un papel clave en la cultura de Salobreña, como foco, junto con la Biblioteca, de la literatura en el pueblo. Antonio organiza varias actividades – presentaciones, un club de lectores, charlas – con mucho éxito. Me impresiona cuantas horas trabaja. Sin empleados, siempre está, e incluso fuera de las horas normales de las tiendas. Como dice Antonio, “Es un punto de encuentro, de conversación, de descubrimiento y de comunidad. Aquí la gente viene a buscar una historia, pero también un consejo, una charla, o simplemente a sentirse parte de un espacio donde la cultura está viva.” Como resultado, tiene un público muy fiel que incluye gente de Motril, el Vallé de Lecrín y la Alpujarra. También envia libros por toda España.

Destaca el apoyo que da a los autores y autoras locales. Antonio me ha apoyado desde que salió mi primera novela, Secrets of the Pomegranate, en 2015. He presentado allí mis tres libros (los dos en inglés y la traducción al castellano de The Red Gene (El Gen Rojo). En este pequeño pueblo, Antonio ha vendido más ejemplares que cualquier otra librería e incluso en Amazon. Invita a los autores locales a participar en mesas redondas (como durante el festival Arte Peajos de 2023) o en las reuniones del Club de Lectores cuando hablan de sus libros. Por ejemplo, este mes de enero hablamos de Comedrejas, un libro de Alejandro Pedregosa, con la presencia del autor. Ya presentó ese libro en la librería el año pasado.

Pregunté a Antonio cuando y cómo empezó el negocio. Dijó que lo montó en 2011 cuando quedó desempleado y buscaba una idea de negocio después de trabajar cinco años en una tienda de decoración. Había estudiado filología inglesa y siempre le interesaba cosas relacionadas con los idiomas y la literatura. Vió que en Salobreña no había una librería y decidió montar una, porque tenía mucha relación con el público con origen inglés que vivía en la zona. La idea original vinó de una librería de segunda mano que había visto en un pueblo de Cádiz. Su idea fue que la mayor parte del negocio fuese libros en inglés pero cuando estaba en contacto con distribidores y editoriales, ellos le sugiereron que también trate en libros españoles.

Ahora, la venta de libros nuevos, la gran mayoría de ellos en español, forma la base del negocio, pero también sigue vendiendo una amplia selección de libros en inglés porque tiene muchos clientes de habla inglésa. Sin embargo, sigue la venta de libros de segunda mano en varios idiomas como una parte del negocio. Antonio no pone un precio, deja que la gente pague lo que quiere, porque, señala, son libros que él no ha pagado, pero sí que ayudan a mantener funcionando el negocio. También la gente puede cambiar un libro por otro, y eso siempre es gratuito.

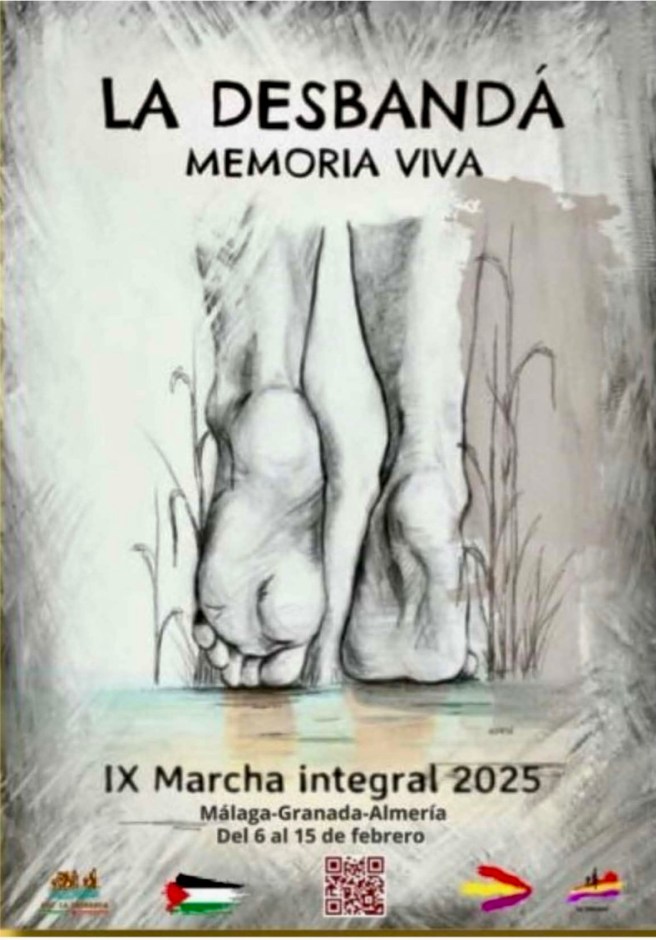

Antonio está muy metido en la vida y cultura de Salobreña y la Costa Tropical. Es jurado con dos otros en el Certamen Literaria de la Asociación de la Desbandá, la conmemoración anual de la retirada desde Málaga a Almería en febrero de 1937. Tiene historias de su propia familia aunque no le queda tiempo para escribirlas. Escribe reseñas de libros o artículos, eso sí.

Me impresiona mucho su conocimiento de los libros y de su clientela – algo que facilita hacer recomendaciones. “Es lo que nos diferencia a los libreros de librerías pequeñas de las grandes superficies o de las librerías online, el tener trato directo con el cliente y conocer lo que estás vendiendo. Tienes que leer mucho y saber qué es lo que puede gustar a tus clientes.” Su genero favorito coincida con el mío. “Me gusta mucho las novelas realistas, pueden estar ambientadas en la actualidad o en algun periodo anterior, novelas historicas pero que cuenten historias que si no han ocurrido de verdad, podrían haber ocurrido.”

Está claro que Antonio está totalmente entregado a su trabajo y que cuenta también con el apoyo de su mujer e incluso de sus dos hijas, que asisten en casi todas las actividades que organiza. Subraya Antonio la importancia que tiene su apoyo, al principio sobre todo, porque si el negocio no habría ido bien ellas también sufrieran. No es fácil vivir de un pequeño negocio como una librería. Dice Antonio que el márgen para libros es muy pequeño. “Por eso, hay que vender otras cosas, como materiales escolares, juegos y papelería.” Durante la pandemia, tuvo que pensar como seguir. Hacía pedidos online pero la sobrevivencia era muy precaria. Además, se preocupaba por si la gente estuviese perdiendo el hábito de comprar en tiendas físicas. Estaba acostumbándose a comprar online. Pero es evidente que la gente haya vuelto, y cada vez mas. Seguro que tiene mucho que ver con su dedicación y su buen trato con la gente.